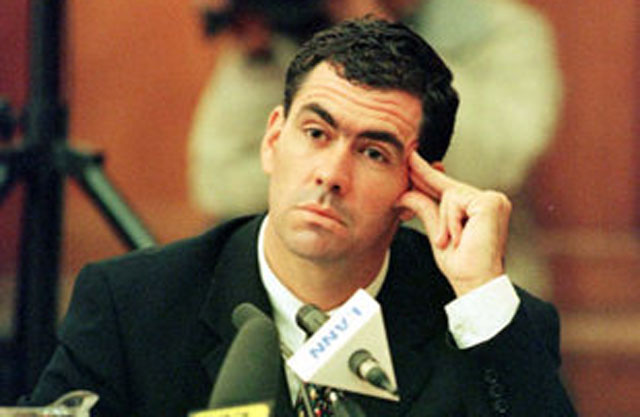

Hansie Cronje: Hero to zero

Fallen hero

When South African cricket captain Hansie Cronje was accused of involvement with Indian bookmakers in April 2000, he said the allegations were completely without substance. Yet it took less than 90 hours for Cronje’s statement of wounded integrity to become a guilt-wracked confession of dishonesty.

Six months on the situation has only got worse. Even Cronje’s admissions have been found to be riddled with falsehood. The King Commission, investigating corruption in South African cricket, uncovered evidence of bribery reaching back to the Centurion Test match against England in 1999. Even now there are still rumours that not every crime has seen the light of day.

Life ban

Cronje was banned from cricket for life by the United Cricket Board (UCB) of South Africa on 11 October 2000 – preventing him from any involvement in the game that has been his life. He is, however, set to launch an appeal so he can work in cricket journalism and broadcasting.

Cronje’s future is uncertain. But what is clear is that cricket does not want him. Once the most admired cricket captain in the world, and an emblem of the new South Africa, Cronje’s stock has now fallen too low for him ever to be taken seriously in the commentary box. Nor will a rash of publicity, in the form of interviews and autobiographies, restore him to credibility.

Media attention can only serve to remind people of the greed that caused him to sin, says Pastor Ray McCauley, the man he turned to when things first got tough. ‘My advice to him would be to stop, stop right now…it is important for him to be seen as somebody that is very repentant for what’s happened and also that he needs to put back into the nation something other than just the fact that he’s going to walk away from it.’ (Wisden Cricket Monthly, 31 August 2000)

Salvation

The symbolism that made Cronje’s fall so devastating, however, could ultimately save him. It is impossible to forget his achievements as cricket captain and ambassador for the nation, leading his side to World Cup victory in 1995 and fighting to raise the profile of black cricketers in both the national and international arenas. If he has faltered, so has his nation. South Africa, too, is struggling with the reality of crime after the euphoria of freedom.

Cronje’s career can and should be saved. He has lived out both successes and failures larger than life, and the people of South Africa have felt them as their own. Now he can be their story of rehabilitation, an emblem of hope for the future and recovery from the past. When visiting Cronje’s home recently, Nelson Mandela told him he must turn ‘tragedy into triumph’. He can do this by taking a public goodwill role, forgoing personal publicity and regaining his famous pride in his work. Where better than the Truth and Reconciliation Commission?